1. Introduction

As any developer will testify, trouble-shooting bugs can be time-consuming and ungratifying. It is also wasteful - time you spend debugging is time you don’t spend adding new features. So it makes sense that anything you can do to streamline this process is worth considering.

One simple approach that can go a long way is to use domain-specific exceptions. In a nutshell, this means making your exceptions mean something. For example, rather than returning a NoResultException exception, you return a NoSuchClientFound exception, adding some domain context (such as the ID or the name of the client) in the error message.

It turns out that this technique works equally well for automated acceptance tests, and is equally worthwhile: trouble-shooting failing acceptance tests, and routing out flaky ones, is often even more time-consuming and wasteful than debugging application bugs.

In this article, we will see how domain-specific exceptions can be implemented using in Serenity BDD using the Journey Pattern. Serenity BDD is an open source library designed to help you write better, more effective automated acceptance tests, and use these acceptance tests to produce high quality test reports and living documentation. In this article we assume some knowledge of Serenity and its support for the Journey pattern. If you want to learn more about Serenity, check out the Serenity BDD Website. If you want to learn more about how Serenity BDD supports the Journey Pattern, take a look at the relevant chapter in the Serenity User’s Manual.

2. Using Semantic Exceptions to make expected behavior clearer

Imagine we are working on a Todo application, surprisingly similar to the ones used on the TodoMVC website. Suppose we want to add a new feature to the Todo application: the ability to flag certain items as Important. As part of this feature, we need to be able to filter items so that only the important ones appear. The following test uses the Journey Pattern implementation in Serenity to describe this behavior:

@Test

public void items_should_not_be_flagged_as_Important_by_default() {

givenThat(james).wasAbleTo(OpenTheApplication.onTheHomePage());

andThat(james).wasAbleTo(AddTodoItems.called("Walk the dog", "Put out the garbage"));

when(james).attemptsTo(

Complete.itemCalled("Walk the dog"), (1)

FilterItems.byStatus(TodoStatusFilter.Important)); (2)

then(james).should(seeThat(TheItems.displayed(), is(empty())));

}| 1 | Click on the Complete checkbox for this task |

| 2 | Click on the filter button with a label of Important |

The task that clicks on the right filter button is called FilterItems looks like this:

public class FilterItems implements Task {

public static FilterItems byStatus(TodoStatusFilter status) {

return instrumented(FilterItems.class, status);

}

private final TodoStatusFilter filter;

protected FilterItems(TodoStatusFilter filter) {

this.filter = filter;

}

@Step("{0} filters items by #filter")

public <T extends Actor> void performAs(T theActor) {

Target filterSelection = FilterSelection.FILTER.of(filter.name()) (1)

.called("filter by "+ filter);

theActor.attemptsTo(Click.on(filterSelection)); (2)

}

}| 1 | How do we find the filter button corresponding to the filter we want to click on |

| 2 | Click on this button |

Naturally, this test will fail, as the Important filter button does not exist yet. When this fails, Serenity throws a NoSuchElementException exception:

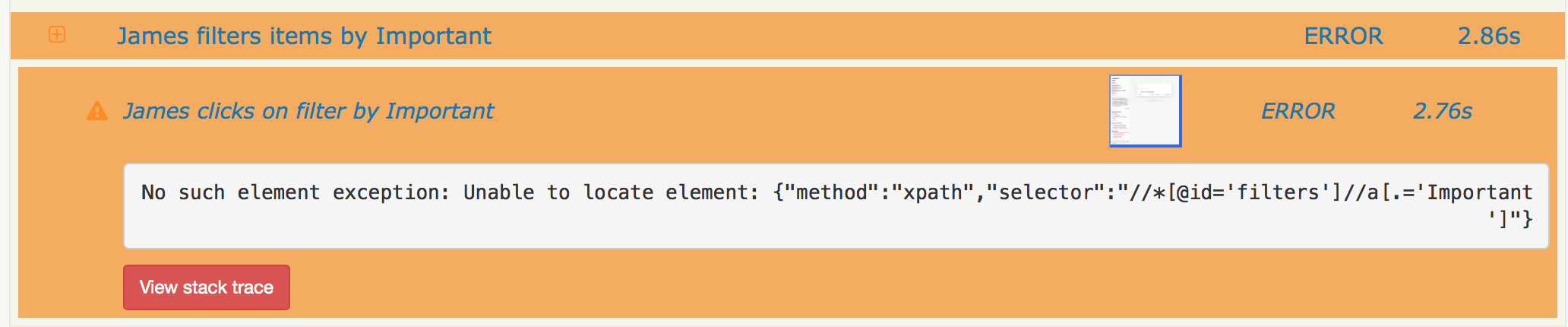

org.openqa.selenium.NoSuchElementException: Unable to locate element: {"method":"xpath","selector":"//*[@id='filters']//a[.='Important']"}

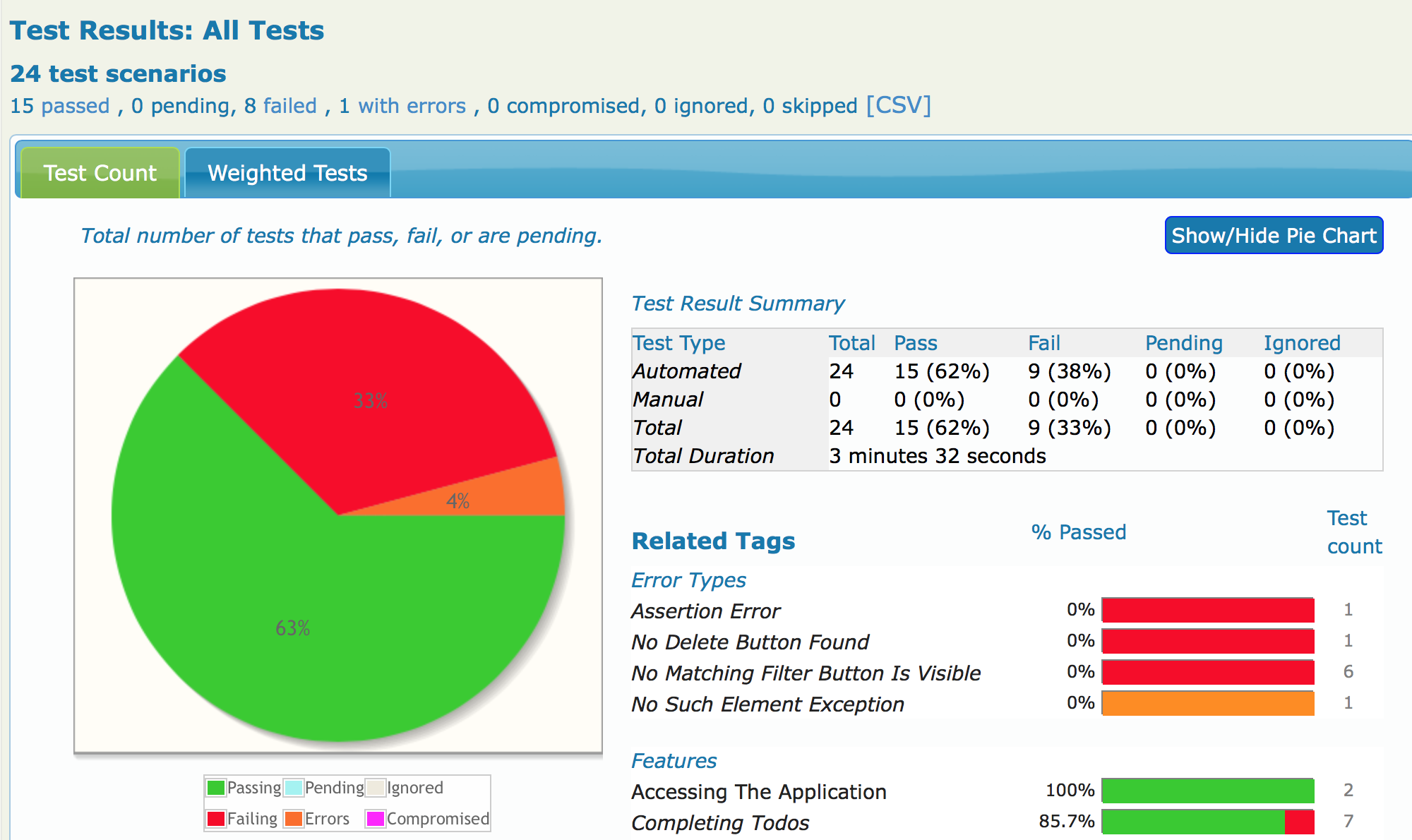

When it comes to triaging test failures, Serenity takes a first step for you by trying to distinguish between failures and errors. Failures are meant to indicate that the application is not behaving as expected, whereas errors indicate a potential problem with the test itself. For example, an AssertionError will appear as a failure, since these are caused by failed assertions about the expected state of the application. WebDriver exceptions, on the other hand, are more ambiguous: they might indicate an error in the test itself (for example, an incorrect CSS selector), or they might indicate the failure to find an expected field or value. By default, Serenity will report exceptions like this as errors.

In the Serenity test reports, the failing test shown above (caused by a NoSuchElementException exception) will appear as an error, in orange, to indicate a potentially broken test in need of fixing.

The problem with this exception is that it is somewhat generic, and we need to sift through the XPath expression to really figure out what is going on. In addition, it is misleading - this test correctly demonstrated that the feature described (the Important filter) is not present in the application.

One way we could improve this report would be by making the exception was a little clearer. For example, we could define a special exception to describe the problem:

public class NoMatchingFilterButtonIsVisible extends AssertionError { (1)

public NoMatchingFilterButtonIsVisible(String message, Throwable cause) { (2)

super(message, cause);

}

}| 1 | We extend the AssertionError exception to indicate an application failure and not a test failure |

| 2 | Custom exceptions need a constructor with a message and a cause |

We can now modify the performAs() method in the FilterItems class to check that the filter button we want to use is indeed available. We can do this using the should() method of the Actor class. In Serenity BDD tests that use the Journey Pattern, the should() method is normally used for assertions, but in this case we are using it to check preconditions. We would use the orComplainWith() method to tell Serenity what exception it should throw if the check fails (optionally with a useful error message).

The new version of the performAs() method looks like this:

@Step("{0} filters items by #filter")

public <T extends Actor> void performAs(T theActor) {

Target filterButton = FilterSelection.FILTER.of(filter.name())

.called("filter by "+ filter);

theActor.should(seeThat(the(filterButton), isVisible()) (1)

.orComplainWith(NoMatchingFilterButtonIsVisible.class, (2)

getMissingFilterButtonMessage())); (3)

theActor.attemptsTo(Click.on(filterButton));

}

public String getMissingFilterButtonMessage() {

return String.format("Missing filter '%s'", filter);

}| 1 | Check that the filter button for the requested filter is visible |

| 2 | If this check fails, throw a NoMatchingFilterButtonIsVisible exception |

| 3 | Create a custom message for the exception |

This code uses the static the() method from the WebElementQuestion class to match a Target value with a matcher from the WebElementStateMatchers class. The WebElementStateMatchers class provides a large number of Hamcrest matchers, including isVisible(), isEnabled(), isSelected(), containsText() and many others, which check the state of a Selenium element.

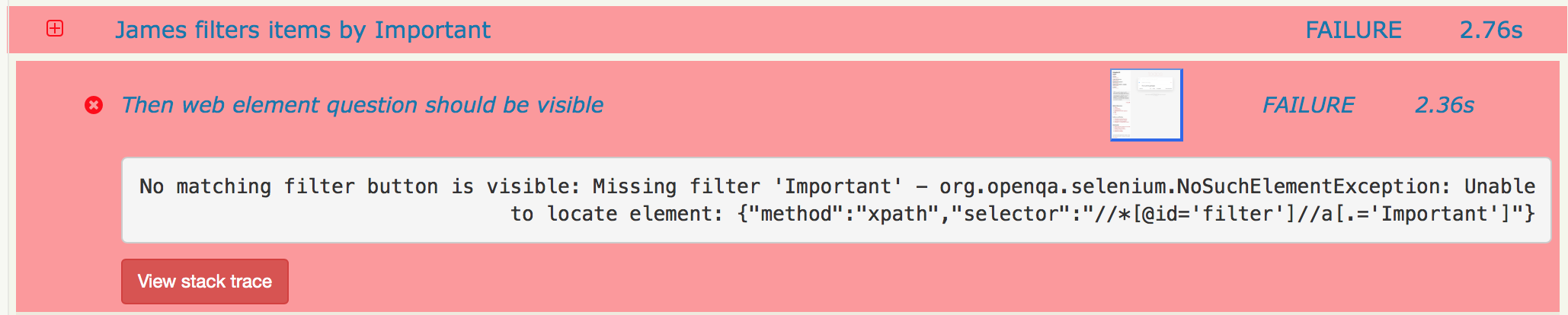

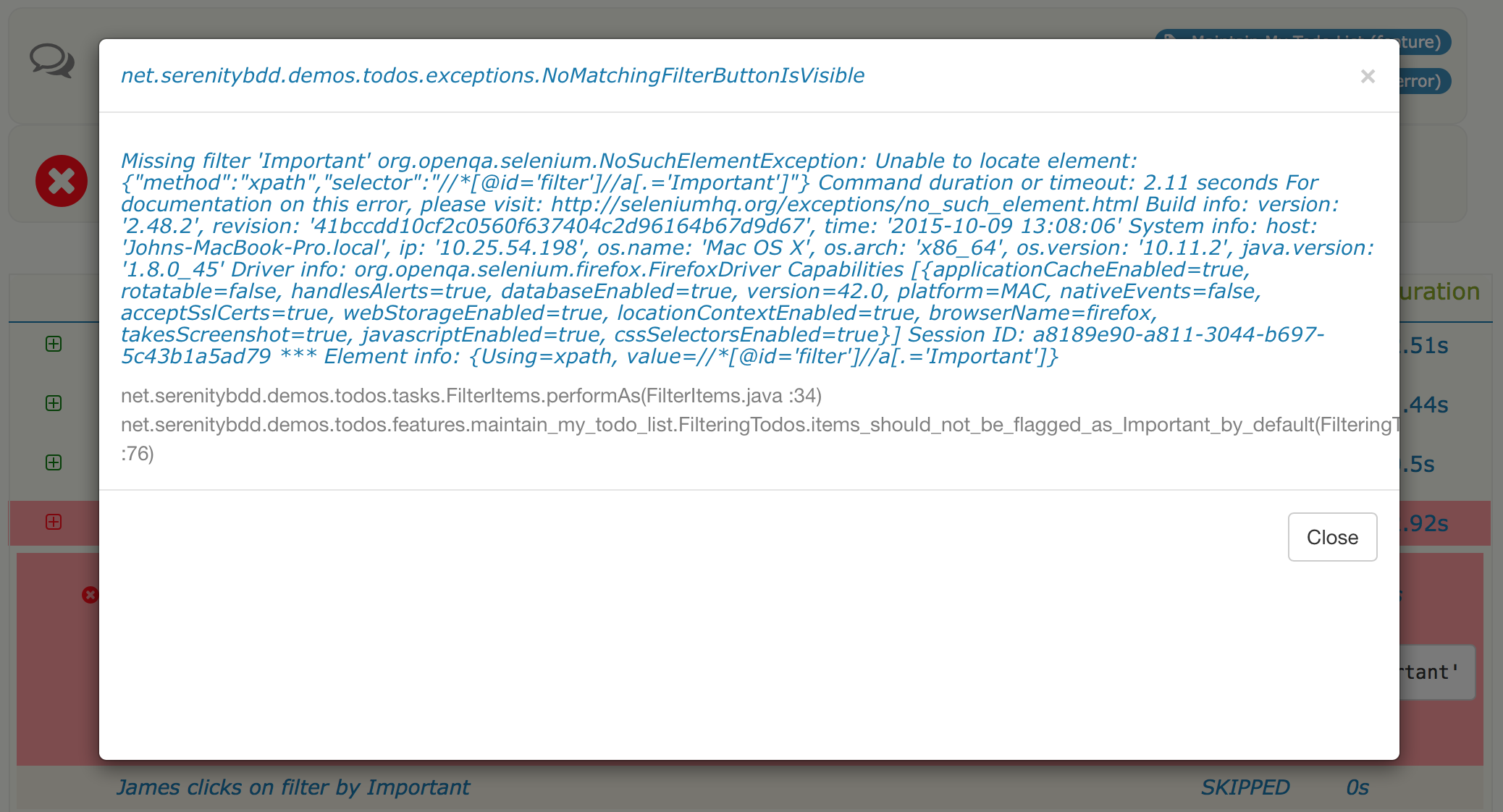

Now, when this test fails, the error report now describes a failure in business terms rather than technical ones:

Serenity also provides more details about the failure in the Stack Trace view:

3. Finer control over exception types

By default, Serenity treats exceptions derived from AssertionError as test failures, and any other exceptions as errors. However, you may sometimes want to flag errors other than assertion errors as application failures. The easiest way to do this by making your exception implement the CausesAssertionFailure interface.

You can also customize the way Serenity reports exceptions using system configuration properties. You can provide a list of exception classes that should generate a test failure in the serenity.fail.on system property. For example, if you wanted a test failure (rather than a test error) on reflection errors, you could add the following line to your serenity.properties file:

serenity.fail.on = java.lang.IllegalAccessError, java.lang.NoSuchMethodExceptionSerenity also lets you flag errors that are caused by problems beyond the scope of the tests, for example if the database crashes when you use a remote service to inject test data. We refer to tests that fail for reasons unrelated to the feature being tested as compromised tests, since you can’t say anything for certain about the acceptance criteria under test other than that you were unable to test it.

You can tell Serenity what exceptions should be reported as compromised tests using the serenity.compromised.on property:

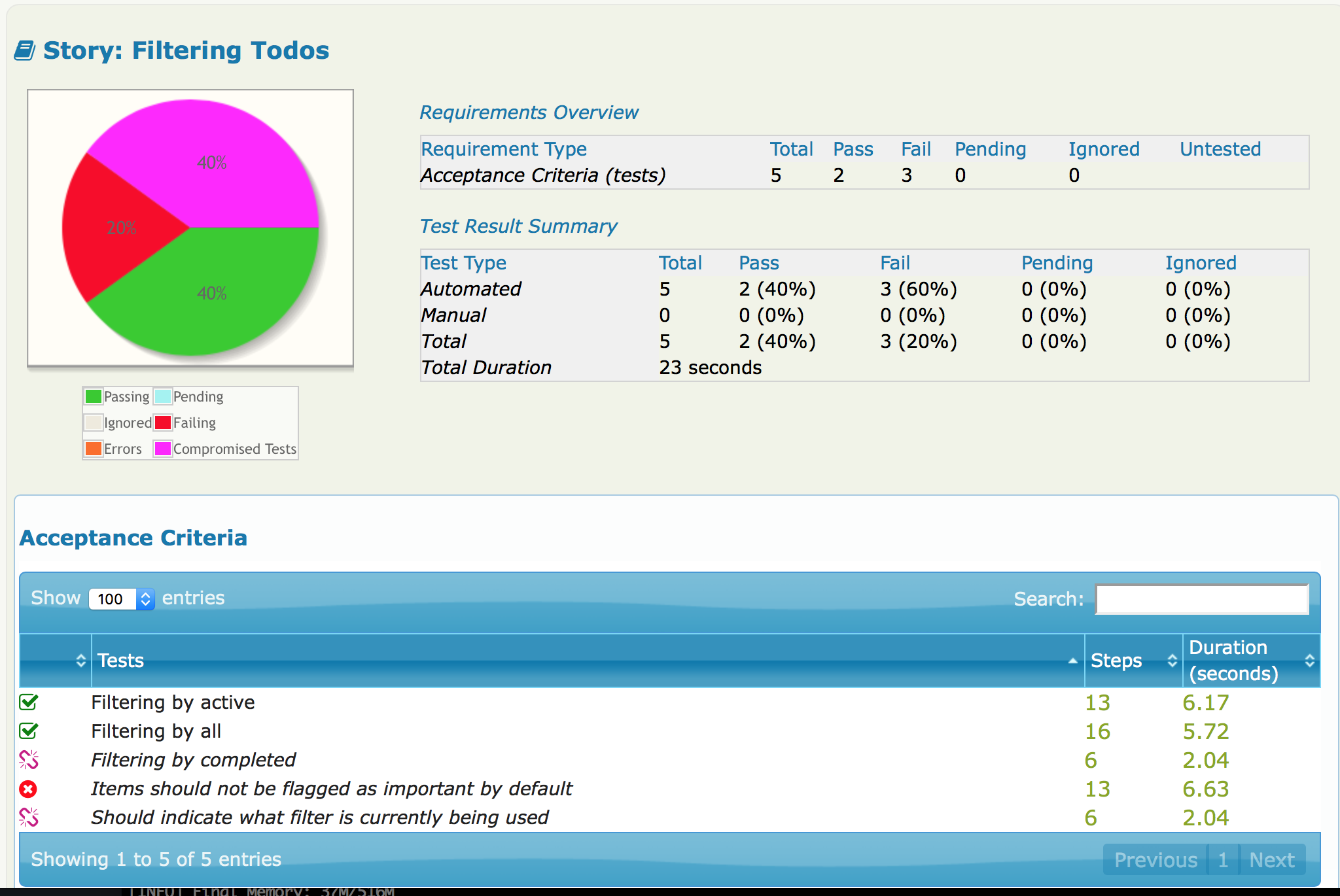

serenity.compromised.on = java.sql.SQLExceptionCompromised tests appear in purple in the test reports:

4. Using Semantic Exceptions with other Serenity tests

In this article we have seen how the orComplainWith() method provides a very readable way to throw domain-specific exceptions using the Journey Pattern. However, from a reporting perspective, Serenity doesn’t much care how you throw the exceptions. So, using a conventional Serenity step library method, you could simply throw the exception yourself:

@Step

public void filter_items_by_filter(TodoStatusFilter filter) {

if (!homePage.isElementVisible(By.xpath(FILTER_PATH))) {

throw new NoMatchingFilterButtonIsVisible("No filter button found for " + filter);

};

...

}This will have exactly the same output in the Serenity reports.

5. Conclusion

Domain-specific Exceptions are simple but effective technique to improve test failure reporting and streamline trouble-shooting and triaging. Even if this test does fail for technical reasons (for example, if the ID attribute used to find the filter buttons changes), a domain-specific exception gives more context and lets you express the intent of what you are trying to do, which in turn makes it easier to figure out what went wrong.